On that Monday the residents of these islands and of much of Puerto Rico were picking up the pieces after the storm, which had taken about 200 lives in the British Virgin Islands, at least 211 on Puerto Rico, and five to six hundred in the Danish West Indies, mostly on St. John and St. Thomas. In the BVI the sinking of just one ship, the Royal Mail Steam Packet Rhone, had taken 125 lives.

Throughout the Virgins, the storm had destroyed public facilities and buildings on many plantations and had ruined most crops. In St. Thomas harbor alone 60 vessels were sunken or grounded.

But even as the survivors were desperately occupied – finding shelter for displaced people, clearing rubble, salvaging the many shipwrecks from harbors and shorelines, treating sick people, addressing unsanitary conditions in order to prevent the spread of yellow fever and other diseases, and resolving a myriad of legal issues related to the extreme destruction – other momentous things were going on.

Under tension from the slow but unstoppable motion of the Earth’s tectonic plate, a large fault on the floor of the Virgin Islands Basin was in its final priming for the release of a tremendous amount of energy. Incongruously undeterred by the hurricane and its aftermath and unaware of the natural calamity that was about to befall them, diplomats from the United States and Danish were resuming intense meetings to transfer ownership of St. Thomas and St. John from Denmark to the U.S. To this end, a treaty between the two countries had been signed on Oct. 24. It required ratification by the U.S. Congress and by the Danish Parliament as well as by the voting residents of the Danish West Indies.

U.S. vessels assigned to accommodate these diplomats were shuttling between St. Croix and St. Thomas. The presence of several significant U.S. Navy vessels bore testimony to the importance of these meetings. Two of these were USS Susquehanna, in St. Thomas harbor serving as flagship for the commander of the U.S .North Atlantic fleet, Rear Admiral James S. Palmer, and USS Monongahela, which had seen considerable action during the US Civil War and had just toured St. Thomas and St. John before delivering commissioners to Frederiksted harbor.

By Nov. 18 the Royal Mail Steam Packet La Plata had arrived in port bearing a letter from Danish King Christian IX informing the citizens of the transfer that was pending their ratification, at least as a courtesy. That afternoon, it was anchored near Water Island, refueling with coal and taking on cargo from tenders tied up alongside.

Then, around 2:50 p.m., the seafloor fault ruptured and released energy at least equivalent to 32 million tons of TNT, more than 1,000 times the explosion of the Nagasaki nuclear bomb. Today its magnitude is estimated as having been between 7.2 and 7.5 on the Richter scale.

Houses collapsed, church steeples were toppled, landslides disturbed the hills, and many people were injured. Terror spread throughout the population. The earthquake’s shock caused ships at anchor to “quiver and rock.” Unsure of what they were experiencing, crewmen checked their vessels for likely causes.

But only a few minutes would pass before they would find themselves facing the ultimate threat – a tsunami that had been generated by the quake. From the earthquake’s epicenter near the center of the Virgin Islands Basin, the first tsunami wave would have taken fewer than than 10 minutes to reach St. John and St. Thomas and as few as 5 to 6 minutes to Frederiksted. owing to this trajectory traveling through deeper water. The only warning would have been the violent behavior of the sea – rushing onto the land, sometimes as a cresting wave, all the while emitting a frightening roar.

As Admiral Palmer, aboard Susquehanna, described it, “… the extraordinary spectacle of a heavy wall of sea some twenty feet in height, apparently distant about three miles, was coming towards the harbor with terrible power”.

Whereas Admiral Palmer in St Thomas experienced the wave advancing onto the land first, in Frederiksted, Monongahela’s navigator, G.F. Harrington, wrote that the water first withdrew from the shore between Butler Bay and Sandy Point “with astonishing rapidity” and shortly afterwards took the ship towards the beach with such speed that casting the anchor only caused damage to the deck.

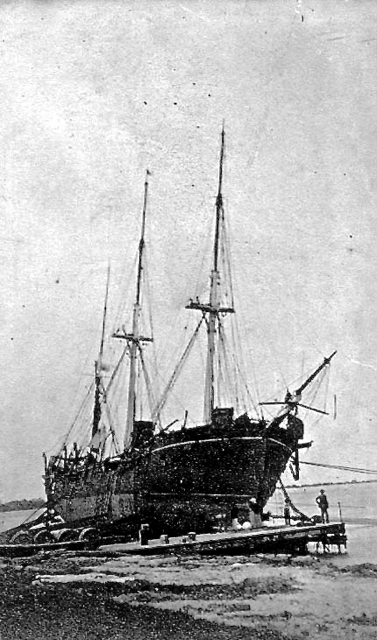

Damaged and adrift the vessel was washed inland with enough water depth that the crew could attempt to sail out over the beach. But a “curling wall of water about 15 feet high” caught Monongahela and deposited her on the rocky shore. There it remained until the U.S. Navy repaired and refloat it six months later. At least three men had lost their lives aboard.

Typical of most tsunamis, this event had consisted of a series of waves, and the wreck-strewn waters around the Virgin Island Basin returned to normal before the afternoon had ended. However, it wasn’t over for other shores. Without the advantage of the advanced warning from the causative earthquake, residents of other Caribbean ports suffered their own losses. Lives were lost in Guadeloupe where, in some places, the sea rose higher than it had in the Virgin Islands. Computer models of the 1867 tsunami show it traveling outward in all directions from the Virgin Islands Basin and reaching Grenada in about 90 minutes. This is consistent with actual observation. St. Georges harbor was greatly disturbed, vessels were tossed around and coastal damage was sustained.

Earthquakes continued to occur, all that day and well into the New Year. So upsetting were these aftershocks, that for any weeks many residents feared sleeping in homes made of stone, brick, coral and other masonry, preferring makeshift tents. Monongahela’s crew allowed some of its sails to be used for this purpose.

Outcomes of the Nov. 18 earthquake and tsunami were many and varied, but loss of life was mercifully minimized, especially when compared to the deadly hurricane 21 days earlier. In the Danish West Indies, about 30 people perished, most of them on ships or on the shore. The time of day, 3 p.m., was probably most fortuitous; although the harbor was busy, most working people would be found inland and upland, tending to farms and plantations. The same scenario today can be expected to be tragically opposite, with thousands of residents, many of whom sleep in homes well above tsunami danger zones, descending to the shoreline for daytime work in shops, government buildings, airports, marine recreation and even in some schools.

The number of fatalities may have been minimal but the economy took a second beating, as coastal shops, warehouses and infrastructure were swamped and as recovery from hurricane damage was set back substantially. Further, the inevitable outbreaks of yellow fever and other diseases brought more fatalities.

It isn’t known how many, but more American sailors lost their lives to the fever than to the wave. Monongahela would lose several more seamen before it could leave Frederiksted in May 1868.

Today the remains of nine of them rest in a grave in the Frederiksted Lutheran Church yard. Other victims of disease included Admiral Palmer himself, who succumbed to the fever just 20 days after he had reported proudly to the Secretary of the Navy that tsunami damage to his ship had not been significant.

With respect to the negotiations for the transfer of St. John and St. Thomas, some have suggested that the Oct. 28 hurricane followed by the Nov. 18 earthquake and tsunami were major reasons the islands would remain untraded until 1917. But, with the U.S. in reconstruction following its Civil War, the assassinated President Abraham Lincoln succeeded by a much-harassed President Andrew Johnson, and the purchase of Alaska the same year, other political and economic considerations can be cited more confidently.

What is more certain is that the same earthquake occurring at the same time and generating a tsunami in the same way today could have unimaginably tragic consequences. The timing of earthquakes and tsunamis is unpredictable. We know that our region is as earthquake-prone and tsunami-prone today as it was in 1867.

Remembering 1867, we can conclude that the current push for “tsunami-readiness” by the Government of the Virgin Islands, joined by educators and members of the private sector, is very well advised.

Roy Watington, retired University of the Virgin Islands professor of physics, serves as subject matter expert on ocean observing systems and on coastal hazards. He has co-authored "Disaster and Disruption in 1867," a collection of accounts of the hurricane, earthquake and tsunami of 1867.