By the time it got to Canada, 149 people had perished, 54 in Haiti alone. Assisted by a full moon at high tide, it had flooded streets and lower floors throughout lower Manhattan, filling commuter train tunnels with seawater. It produced heavy rains in Pennsylvania and farther inland and dumped heavy snowfalls from West Virginia to Tennessee. By January of this year, the Associated Press had estimated that Sandy had destroyed about 650,000 housing units in New Jersey and New York alone. Across 15 states and the District of Columbia it deprived millions of electricity. At $68 billion in damages, Superstorm Sandy is surpassed only hurricane Katrina among history’s most costly storms.

Oct. 29 was also the impact date of another memorable hurricane – 145 years earlier – right here in these islands. In contrast, while it was a more compact storm and affected fewer different communities it turned out to be much more deadly. Among the first in the Danish West Indies to become aware of its portent was Brother Warner of Emmaus Moravian mission in Coral Bay, St. John.

“We were seated at our dinner table when suddenly the gale came upon us. I rose and looked at the barometer, but as the mercury had only dropped a few lines, I sat down again to finish the meal.” So begins his account, “… The fury of the wind, however, increased so rapidly that we were not left much longer in suspense.” This small but powerful gale would become known as the San Narciso hurricane, named after the feast day of the patron saint of Puerto Rico, Narcissus of Jerusalem. At the moment that Brother Warner was receiving its warnings signs, the storm had already begun dealing severe punishment in the BVI, destroying homes, sinking passenger ships, taking lives.

With its location on the eastern side of St. John, Coral Bay residents, such as Brother Warner and his family, would be among the first residents of the Danish West Indies to be dealt the punishment that the BVI was still receiving from this unexpected storm. San Narciso would rampage through the northern Virgin Islands, Virgin Gorda, Salt Island, Tortola, Peter Island, St. John and St. Thomas, then sweep across Culebra and Vieques to the mainland of Puerto Rico, taking many lives at every station. It was apparently as compact as it was intense, because neither St. Croix or Anegada are reported to have been severely affected.

It had been the ninth tropical storm for 1867, tracking persistently due west but holding at 19° North of the Virgin Islands until the last minute when it dipped to the latitude of St. John. Several barometric pressures were recorded during the storm with the lowest credible observation being 28.10 inches of Mercury (952 millibars). Evaluating the many reports filed, scientists today have concluded that San Narciso hit the BVI with winds estimated at between 100 and 110 mph. San Narciso has been ranked retroactively as a category 3 storm.

Disaster at Sea

In 1867 the Royal Mail Steam Packet, RMSP Rhone was only two years old but had already proven itself in severe storms. It was a big ship – 310 feet long with two masts and could carry as many as 310 passengers. Departing from the common side-paddle design of the day, it was one of only two in the world that used a brass screw propeller to deliver the power rearward from its steam engine, and it could do 14 knots (16 mph). As the storm came up, passengers were being transferred from the Conway, a smaller vessel near Peter Island. Both were being refueled. Coaling and passenger transshipment had been moved from the usual station at St Thomas because of concern about yellow fever in that harbor.

Both vessels stoked their boiler to have power, just in case. As the storm intensified the Rhone tried unsuccessfully to raise its anchor but had to cut it free near Peter Island. The first half of the cyclonic storm was apparently not its most destructive. But anchors were dragging and both captains feared being grounded on Peter Island. The Conway headed for Beef Island, Tortola. Then diminished winds inside of the eye of the storm gave everyone a brief respite, and around 12:30 pm the Rhone made for the open sea. The respite didn’t last quite one-half hour and the winds in the hurricane’s second half changed to south-southeasterly. These pushed the Rhone towards Salt Island. However powerful its engines may have been, the bigger ship was unable to avoid being dashed on the rocks and broken. Water rushing into its hot boilers caused an explosion that split the Rhone into two parts. It sank at the southwest end of Salt Island, taking 125 people to the bottom. The fore mast protruded above the surface and a few crewmen clinging there were rescued the next day. The less powerful Conway was badly mauled, lost its funnel and was run aground at Tortola. Although it could be refloated, additional passengers had lost their lives there.

Up until about 2 p.m., the BVI and St John were still experiencing the storm’s greatest fury. By the time it moved on, the Sanct Thomas Tidende reported that Virgin Gorda had lost about 100 homes, 60 out of the 123 houses on Tortola were destroyed, most sugar estates were damaged, with all crops blighted and 37 lives lost on Tortola, two on Peter Island.

Next came St. Thomas, which felt the storm’s greatest fury between 2 and 3 in the afternoon. Winds may have been diminishing somewhat because San Narciso was a category 1 storm by the time it reached Puerto Rico. But the destruction was greatest here, perhaps because of the developed infrastructure, greater population and large number of ships in harbor. “The town of Charlotte Amalia is frightful to look at…”, wrote a correspondent to the St. Croix Avis, “There is scarcely one building, whether old or new, left uncovered and many … reduced to atoms!!!”

Estimates varied widely – up to 80 – but a least 60 ships were sunk in harbor or washed ashore, including the very large and world-traveled British Empire. It would be auctioned for $65. A diving bell from Hassel Island was lifted and carried one-quarter mile to land on St. Thomas, and all of the major churches stripped of their roofs. George Knaggs, a purser on the Royal Mail Steamship RMSS Solent, reported that, when his vessel got to St Thomas on the 31st, he found the lighthouse at Muhelfelds Point destroyed, along with the gas works and the offices of the Tidende. He was informed that 360 people had already been buried.

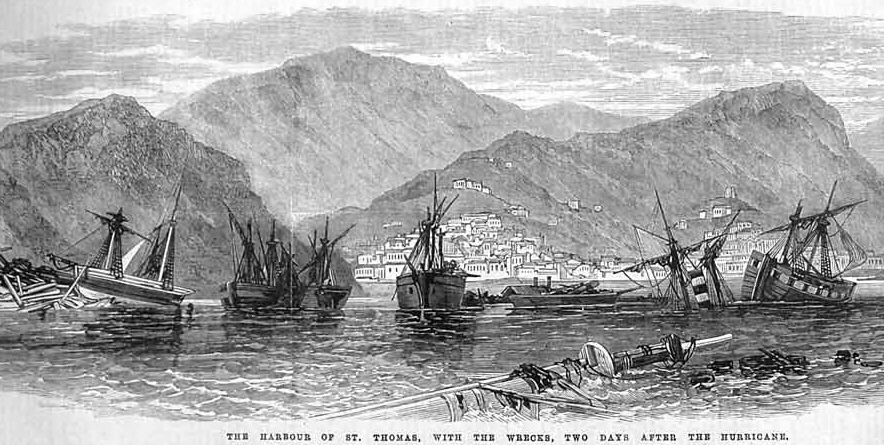

The following description in the Lyttelton Times fits the lithograph published in Harper’s Weekly and in the Illustrated London News and shown above, “The scene in the harbor is frightful. In every direction masts of vessels appear above water, standing up, one might say, like blades of grass in a field…”. Knaggs suggested, “… The whole effect will be to utterly ruin the island and almost depopulate it.” Little did he know that within three weeks the great earthquake and tsunami of 1867 would take a turn towards such a consequence. But, by the time it moved on to the west, the hurricane alone would have claimed at least 500 lives in the British and Danish islands.

San Narciso left St. Thomas and reached Puerto Rico in the late afternoon and devastated many parts of that island as well. It killed more than 200 people, displaced people from their homes and damaged crops. This occurred at a time when Puerto Rico was aching under Spanish rule. Mistreatment and general dissatisfaction were feeding thoughts of revolution. Then came the storm, and the impoverished people suffered even more. So depressing were these effects on the island’s workers that it has been suggested as the final straw for the rebellion against Spanish rule that would break out near the town of Lares starting Sept. 23, 1868. It happens that St. Thomas had been one of the safe places where revolutionary leader Ramón E. Betances and others could meet to consider revolt. Francisco Moscoso writes that from St. Thomas Betances issued his Diez Mandamientos de los Hombres Libres (the Ten Commandments of Free Men). However, as the revolution started the next year the Danish government contributed to its fate by seizing a vessel containing arms and supplies for the rebels. Unsuccessful, the biggest Puerto Rican revolt against Spanish rule would be remembered as “El Grito de Lares” (the cry of Lares).

After taking an additional 200 lives in the Dominican Republic, San Narciso was weakened to a tropical storm by the mountains and finally petered out over Haiti. Even today, after the Galveston Hurricane of 1900, Andrew in 1992, Hugo in 1989, Marilyn in 1995, Katrina in 2005 and Sandy in 2012, the San Narciso still ranks among the deadliest Atlantic storms impacting North America.

Given the date of the San Narciso storm, one might wonder why thanksgiving for the end of the hurricane season continued to be observed so early. From 1726 to the late ’70s it had been fixed on Oct. 25 and was a government holiday. Even today, in spite of late year events like Hurricane Lenny, which passed St. Croix on Nov. 17, 1999, as a category 4 storm, Hurricane Thanksgiving is recognized on the third Monday in October.