This year we have received below-average rainfall. In fact, our streams and guts have not heavily flowed since the 2017 hurricane season. On the surface of the islands, everything appears lush and green. The greenery dominates the environment with its magic of chlorophyll, which converts sunlight into energy in the process of photosynthesis. Those of us who are in tune with nature will notice the absence of certain organisms in abundance this autumn and winter season.

One organism that is usually in abundance this time of the year is butterflies. Recently, I conducted a hike for the St. Croix Hiking Association, which I am a member of, along the beautiful green rolling hills of the east end of the island to Jack Bay, Horseshoe Bay, Isaac Bay, and Small Isaac Bay. As I explained to the hikers, there are no blossoms of Ginger Thomas, the territory flowers of the Virgin Islands covering the hillsides, valleys, and coastal landscapes of the east end of St. Croix.

According to the old people, Ginger Thomas blossom is an indicator of whether you will have a good or poor year sugarcane crop. If about 90 percent of the flowers hold onto the tree, it will be a good year for harvesting sugarcane. However, if about 90 percent of the flowers fall off the tree, then it will be a poor year for harvesting sugarcane. There were no blossoms of flowers covering the historic landscape of St. Croix’s east end with thousands of Great Southern White butterflies gathering the nectar from the Ginger Thomas flowers.

As we hiked along the trail, there were a few butterflies here and there rising in front of us to the blue sky as we walked near them on the dirt path of one of St. Croix’s most beautiful landscapes. The Great Southern White butterfly, whose scientific name is Ascia monuste eubotea, is usually very common and abundant during this time of the year, signaling in the Christmas season.

They are whitish in color with a wingspan of about 3 inches. When the adults open their wings, they are white with brown or gray markings around the border. As they fold their wings, the color is yellowish-white with brown markings at the border. Butterflies and rain coincide with one another. It is a natural phenomenon in nature. The old people, as we know all too well, were much closer and more tuned in to nature.

It is this kind of traditional knowledge I try to pass on to the next generation of Virgin Islanders. In a normal rainy season, many of the dormant eggs of the butterfly would have hatched into caterpillars. They would rapidly mature on an abundance of new growth of vegetation and formed pupae. We did see one or two worms, but nothing much to talk about. Within the pupae, ugly worms appear on everyone’s gardens, lawns, or open fields and metamorphose into butterflies.

If we had gotten sufficient rain, especially during our rainy season, there would have been an abundance of wildflowers blossoming, which creates the perfect environment for caterpillars to thrive. With these caterpillars, all metamorphosed in a short period of time, we would have seen the preponderance of butterflies on the landscape. As a rule, in the middle of December on St. Croix, the heavy rains cease. I am talking about a normal year rainy season. Thus, the weather change reflects on the plant community, which also impacts humans and wildlife.

The lifelessness and change of the plant community tinges everything. Only the sensitive eyes of observing nature would have no trouble in detecting changes in the plant environment. With the slowing down of the rain on a normal year in December, the vegetative community has received its yearly signal to close shop. On a normal year rainy season (I am talking sufficient rain), certain plants are important to certain species of butterflies. In the hills of Estate Annaly, there is a beautiful little, red-flowered milkweed plant known by botanists as Asclepia curassavica.

This plant is poisonous due to the milky sap in its leaves. However, this plant is one of the favorite foods for our most beautiful butterflies in the Virgin Islands, the Danaus megalippe. In the book “Ay Ay: An Island Almanac” by the late naturalist George A. Seaman, he describes the relationship between the monarch butterfly and the milkweed plant by saying:

“This large, strong-flying reddish and black butterfly along with its conspicuous caterpillar, makes no particular effort at hiding, apparently knowing its enemies will shun it as an undesirable tidbit. But most interesting of all is that wild relationship between our little milkweed, the monarch butterfly and the gorgeous constellation Scorpio.” And so, the question might arise as to why only one population peak of caterpillars and butterflies.

This question can only be answered by the ecological check and balance of nature. We have several species of butterflies in the Virgin Islands. All populations of butterflies are controlled to some extent by parasites, predators, and diseases. When butterflies and caterpillars are few in numbers from what we have observed during hiking along the bays of the east end of St. Croix, parasites of any sort have a difficult time completing a life cycle from one host to the next.

When butterflies are scarce, predators find it more effective to gather more easily found prey. On the other hand, when the butterfly population is low in density, contact between individuals is greatly reduced, thus making disease transmission an infrequent event. When butterfly populations increase, all of the above limiting factors swing into play. Nevertheless, while caterpillars are increasing, predators, parasites, and diseases contribute to their demise and eventually catch up with them and the cycle of the natural world continues.

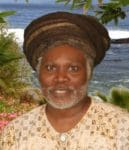

— Olasee Davis is an Extension Professor/Extension Specialist in Natural Resources at the University of the Virgin Islands who writes about the culture, history, ecology and environment of the Virgin Islands when he is not leading hiking tours of the wild places and spaces of St. Croix and beyond.