Where did we leave off? O’ yes, talking about guts of the Virgin Islands. This third part in a series on the guts of the Virgin Islands will take us to the time when the European colonists encountered these islands still in their virgin state. The streams, guts, and small rivers were still flowing year-round, as they were from the beginning of the islands’ geological development. From what we were told by historians, we know that the island of St. Croix particularly remained abandoned and uninhabited around 1515, although there were Amerindians, not in great numbers, still on the island.

You must remember that the Spaniards dominated this part of the Western Hemisphere when the so-called New World was divided between Spain and Portugal with the blessing of the Pope. In 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas between Spain and Portugal divided the rights to colonize all lands outside of Europe, which included the Virgin Islands. Nevertheless, Spain quickly extended its power to the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, claiming the region as its own. The Spaniards had a strict policy of monopolistic trade, forbidding other European nations’ vessels from passing through the waters of the Caribbean.

However, the Northern European maritime countries such as France, England, and then later the Netherlands rejected the Spanish trade policies in the New World. They too wanted to rape these islands’ natural resources and enslave the indigenous people of the Western Hemisphere. As a result, wars often broke out among different European nations to control the natural resources of the Caribbean islands. It was for this reason that St. Croix through its history had seven flags of different nations controlling its natural resources and using the island as a strategic military location in the Caribbean.

Nonetheless, it was through the colonial history of the Virgin Islands that we have acquired knowledge of their virgin state before they were impacted culturally and environmentally by colonial greed. If it was not for the European colonists and others, though they might have been biased in their findings, who wrote about the island’s natural environment, we wouldn’t have known about guts, streams, and small rivers in the Virgin Islands. It is through Europeans’ and others’ writings that historians, archaeologists, and others get an understanding of the islands’ natural history and the indigenous people’s way of life in the Caribbean region.

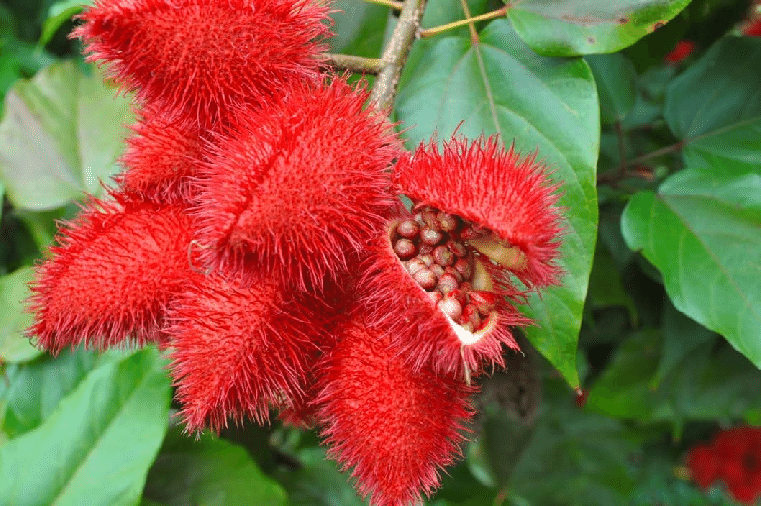

On the other hand, we also learned in history that without the indigenous people of the Caribbean, European colonists might not have survived these islands due to the unforgiving environment and due to various tropical diseases. For example, the Amerindians used annatto (Bixa orellana) daily by painting their bodies to repel mosquitoes. The repellant was made from crushed roucou (annatto) seeds mixed into a castor oil solution. The Europeans used this remedy and used annatto seeds also for food dye.

Nevertheless, St. Croix was a major stopover for many other European powers in the region because of its abundance of forests and sweet water. From 1493, the Spanish owned St. Croix, but never settled the island. They mainly used St. Croix for its natural resources such as timber and the abundance of fish in the surrounding waters of the Virgin Islands. “In 1587, Captain John White stopped there with his three ships for three days in order to take on fresh water and capture sea turtles,” noted the late historian Arnold R. Highfield in his book titled “Sainte Croix 1650-1733: A Plantation Society in the French Antilles.”

In 1629, Monsieur de Cahusac, a general in the French naval army, sailed for St. Croix to take on fresh water on his route to the western Caribbean islands. “He arrived there after a day’s sail and found ‘three or four beautiful rivers with very good water,’” which supplied his fleet with a “quantity of [drinking] water,” noted de Cahusac. He went on and described how beautiful St. Croix was with a length of 14 to 16 leagues and beautiful rivers. Later that year, a group of Frenchmen visited St. Croix to cut timbers for building their longboat, but they were caught by the Spaniards who still owned the island.

Jean-Baptiste DuTertre (1610-1687) was a French blackfriar and botanist. When he visited St. Croix, he wrote: “There is a great number of attractive rivers and springs flowing into the sea…”. When Frederick Moth visited St. Croix in 1734, he wrote: “Found the land on the West End quite lovely and walked about a mile inland to take a look at the famous plantation Le Grange, which is accounted to be the best in the land. The walls of all the buildings are still visible and in part sound, a fine river runs by all through the year.” Today, that “fine river” is called locally Le Grange Gut.

The islands of St. Thomas, St. John, and Tortola also had perennial flowing streams to the sea during the colonial period to early 1960s. Historical documents have reported that streams on St. Thomas provided much potable water for residents from the 16th century through the middle of the 20th century. I can recall as a child swimming in the stream known as DeJongh’s Gut, but actually named after Agnes Brower, thus Brower’s Gut. This stream runs down from St. Peter Mountain and drains into the Charlotte Amalie harbor. DeJongh’s Gut was where women used to wash clothes.

St. John, with its deep valleys and mountainous topography, once had perennial running streams. Historically, many of the larger guts had running water in them. Scientists believed when the forest was cut down during the colonial period for cultivation that the loss of absorbent soil and humus caused the entire water table to drop. However, during heavy rains, these guts can become raging torrents. Reef Bay now has a seasonal waterfall on St. John and is an example of when streams once flowed all year round.

Sage Mountain in Tortola is the highest peak in the British and U.S. Virgin Islands, at 1,710 feet above sea level. I remembered as a child playing in the stream in Cane Garden Bay with my grandmother when she washed clothes in the running water from Sage Mountain. At that time, Cane Garden Bay used to have coconut trees along the coastline. I am talking about the 1960s when Tortola was still feeding themselves and streams were running into the sea constantly. This conversation about guts will continue.

Editor’s Note: Read Part 1 of this series here, and Part 2 here.

— Olasee Davis is a bush professor who lectures and writes about the culture, history, ecology and environment of the Virgin Islands when he is not leading hiking tours of the wild places and spaces of St. Croix and beyond.