It may take another year or more, but the U.S. Virgin Islands is moving to identify public and private properties that lie in its mega-sized flood zone. Then all it will have to do is decide whether (and how) to protect individual structures or whether (and how) to remove them.

A recent New York Times article raised the spectrum of widespread use of the government power of eminent domain – that is, a forced buy out of privately held homes or other structures, to clear flood plains, but responses from local and federal officials to Source inquiries indicate that is an unlikely scenario for the Virgin Islands, at least for now.

In the past, flood control efforts have tended to focus on interior creeks and guts that get clogged with debris, overflow in times of heavy rains, undermine roadways and seep into homes. Various federal and local agencies have been involved in those projects which typically are funded by a combination of federal and local dollars.

But as the consequences of global warming become increasingly apparent, flood control efforts are expanding.

Small island communities are especially vulnerable to rising sea levels and intensified rainfall, two of the widely accepted results of climate change, and experts have been trying for years to document the extent of the threat in various locations, including the U.S. Virgin Islands.

It’s already clear that approximately one-fifth of the territory could be in danger of impacts in the not-so-distant future. About 27 square miles is in the coastal flood plain, according to experts from the Department of Planning and Natural Resources. That represents 20 percent of the total 133.73 square miles that comprise the three major islands, St. Croix, St. Thomas and St. John.

Right now, DPNR is taking what Commissioner Jean-Pierre Oriol called “several preliminary actions.” One of these is to “tweak” local regulations to meet updated national standards for flood control and comply with the National Flood Insurance Program.

Amanda Jackson-Acosta, unit chief for the Division of Building Permits at DPNR, said this may involve everything from setback distances from a stream to required elevations for a building’s lowest floor to regulations for cisterns as well as accommodations for changes to flood zone maps and when a flood zone property receives a certificate of occupancy. In some cases, existing V.I. regulations may be more stringent than federal standards, and in some cases, less.

The Virgin Islands Rules and Regulations were adopted in 1993 and amended in 1998, she said.

“We are currently working with a contractor to have our regulations updated and submitted to the Legislature for adoption by this summer,” Oriol said.

Coastal Vulnerability

At the same time, the department’s Coastal Zone Management Division is working with the University of the Virgin Islands to create a Coastal Vulnerability Index for the territory, the commissioner said.

“There have been other types of hazard indices produced for the territory, such as FIRM [Flood Insurance Rate Map] maps, sea level rise viewers, tsunami inundation zones,” Jackson-Acosta said. “CZM’s index will be the first to provide all of these together.”

“The project is underway,” Oriol said, “and could take anywhere from 12 to 15 months to complete.”

Once regulations are updated and the territory begins to get data from the Coastal Vulnerability Index, “the next step for us will be creating a HAZUS for the territory,” Oriol said. “This is the assessment that captures buildings and critical infrastructure in the flood plain and identifies where mitigation and adaptation will need to be implemented.”

Historically, the islands were developed largely from the outside, in, starting at the shoreline and moving inland. DPNR officials would not hazard a guess as to how many structures may lie in the coastal flood zone but did acknowledge that some of the territory’s infrastructure, such as the Cyril E. King Airport on St. Thomas and Christiansted Boardwalk on St. Croix, are included.

As residents know, the shorelines are also home to the Legislature building and the waterfront/Veterans Drive Highway, both on St. Thomas, and a myriad of other structures, including many private homes and small and large hotels. What types of mitigation and adaptation will the territory consider when dealing with its HAZUS structures once they are identified? Levees or seawalls? Elevating structures? Voluntary removal with compensation to owners? Eminent domain?

“A combination of all of the measures mentioned will have to be considered as there is no one size fits all that will apply to all areas equally,” Jackson-Acosta said.

Besides the political and philosophical drawbacks to the use of eminent domain – or the mandatory purchase of private property for the public good – there are practical considerations. The process calls for fair compensation to landowners and can be prohibitively expensive in some cases.

With few exceptions, both federal and local governments have tended to shy away from its implementation.

However, a lengthy article published in March by the New York Times, documents what it describes as a shift in policy on the federal level. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, a key player in flood mitigation projects, has made some federal grant money contingent on a local jurisdiction’s willingness to use eminent domain, if only as a last resort.

According to the article, some jurisdictions, including Nashville, Brookhaven on Long Island and Okaloosa County, Florida, have agreed. “New Jersey has refused,” and Miami-Dade County in Florida “has yet to agree,” while Atlanta at first agreed and then changed its mind and pulled out of a project in January.

The U.S. Virgin Islands is not currently facing such a choice.

The relocation of property out of a flood plain is indeed one of the options the corps routinely considers when weighing its recommendations for mitigation strategies – but it is only one, according to Milan Mora, chief of the Water Resources Branch of the Jacksonville, Florida District. And relocation can be voluntary. Also, he said, the corps does not get directly involved in relocations; FEMA takes the lead on that.

The Virgin Islands is part of the Jacksonville District, which is within the corps’ South Atlantic Division.

While relocation is “always one of the courses of action [considered],” Mora said, “for the U.S. Virgin Islands projects, we are not recommending relocations.”

Inland Flood Projects

Mora and project manager Zulamet Vega, told the Source about two corps “flood damage reduction” projects for St. Thomas, one involving the Savan Gut and the other at Turpentine Run. Both protracted undertakings date back decades. Both projects received new life in 2018 when Congress included them in a major disaster funding package prompted by the 2017 hurricanes, although Mora said funding for completion is not yet assured for either.

Plans for Turpentine Run call for the replacement of the existing concrete channel, which is meant to carry water away from homes in low-lying Nadir, with another of greater capacity, as well as the construction of levees on either side of the gut by the Bovoni racetrack and improvements to the existing “Bridge to Nowhere” in Bovoni, Mora said.

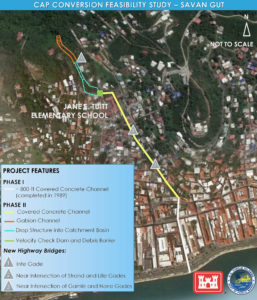

The Savan Gut project was originally recommended by the corps in 1982. It called for the construction of a velocity check dam, with floating debris barriers, above the Jane E. Tuitt School, and a 2,300-foot covered channel or box culvert running all the way down to the Charlotte Amalie Harbor, as well as the replacement of three highway bridges to maintain traffic over the culvert, according to documents from the corps.

In the mid-1990s, Phase I of the Savan project was completed, Mora said. That consisted of an 800-foot culvert running beneath Back Street (Wimmelskafts Gade) to the harbor, effectively acting as a super drain for much of the downtown area. The rest is waiting.

In making recommendations for any flood mitigation, Mora said the corps considers whether a proposed project is feasible from an economic, environmental and engineering prospective.

To put it another way: Are the mechanics such that it will work and that it can actually be done? Is it worth the cost? How will it impact the natural and social environment?

Sometimes the least expensive option is relocation – paying fair market value for homes that are in danger from flooding, as the corps is doing now for a project in Puerto Rico, Mora said. Why spend $60 million to build a levee to protect three homes, he asked rhetorically.

On the other hand, the Savan project, estimated at $80 million if and when it is completed, will cost “peanuts” in comparison with the price of relocating all the buildings at risk of flooding without the project.

“All of a sudden, I’m going to relocate Charlotte Amalie? Where am I going to put it?” Mora said. Better to construct the velocity check dam, the culvert and the rest of the Savan project.

The case was not as clear-cut for the other St. Thomas project, where far fewer existing structures are involved.

“That was a heavy look at Turpentine Run,” Mora said. But in the end, the corps did not recommend relocations.

It will be a while before the territory has to give a “heavy look” at structures in its coastal flood plain, but the countdown has started.

The National Climate Assessment of 2018 included sobering projections for the Virgin Islands. By the end of this century, sea level is likely to rise between two and 11 feet. At the intermediate level for projections, that is, a 6.5-foot rise, all three of the territory’s major towns would be in the inundation zone.